Some kinds of learning happen best when kids aren't segregated by age.

- By

- Parker Barry

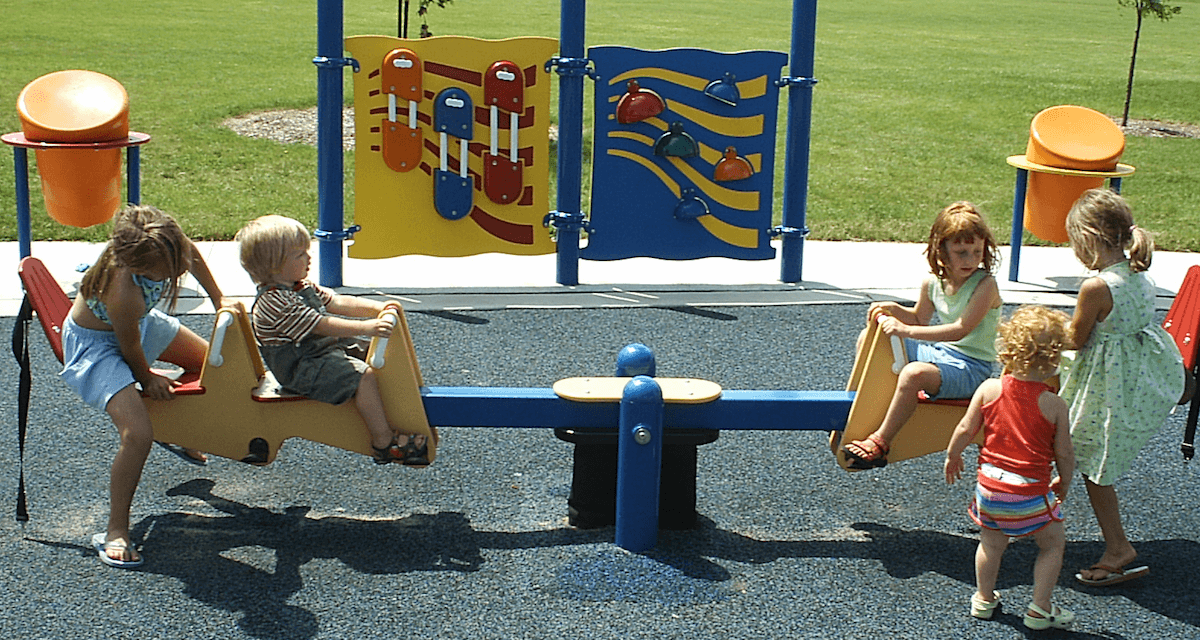

The segregation of children by age is an artifact of modern times. During most of human history, prior to the establishment of our age-graded system of schooling, children nearly always played in age-mixed groups. A typical group playing together might consist of half a dozen children ranging in age from 4 to 12, or 8 to 15. In such groups the older children were often responsible to care for the younger ones.

My own research, and that of others, convinces me that age-mixed play is more conducive to children’s learning than is age-segregated play. Children have far more to learn from playmates who differ from themselves in age and ability than from those who are at their same developmental level. For a full account of research supporting this contention, I refer you to my article, The Special Value of Children’s Age-Mixed Play, published in the American Journal of Play, Vol. 3, pp 500-522 (2011). Here I’ll present just a brief summary of some of the main ideas in that article.

How Age Mixing Benefits the Younger Children

The most obvious benefit of age mixing for the younger children is that it allows them to play at and learn from activities that would be too difficult or dangerous for them to do alone or just with age-mates. Here are two examples.

- Catch. Imagine two 4-year-olds trying to play a simple game of catch. They can’t do it. Neither can throw the ball straight enough or catch well enough to make the game work. But a 4-year-old and a 9-year-old can play catch and enjoy it. The 9-year-old can lob the ball gently into the hands of the 4-year-old and can leap and dive to catch the other’s wild throw. In a world of just 4-year-olds catch is impossible, but in an age-mixed world everyone can learn and enjoy this game.

- Card games. Children under about age 9 generally cannot play formal card games with age-mates. They lose track of the rules; their attention wanders; the game, if it ever begins, quickly disintegrates. But I have often seen children younger than this play cards with older children. The older players remind the younger ones what they have to do. “Hold your cards up so others can’t see them.” “Pay attention to the cards already played and try to remember them.” The reminders are given just when necessary, to keep the game going and to keep it fun for all. In the process, the younger children become better at paying attention, keeping track of information and thinking ahead. These are the foundation skills that underlie what we commonly call intelligence.

Similar suggestions and boosts occur in all sorts of age-mixed games — computer games, writing games, games involving numbers and calculations, outdoor games, informal fantasy games, and rough-and-tumble play. In the name of fun, the older participants naturally, and often unconsciously, erect scaffolds that allow younger ones to stretch and build their physical, social, and intellectual skills.

Young children learn from older ones even when they are not interacting with those older ones. They learn just from watching and listening. From such observations children acquire not just information but also motivation. Children seem to be most motivated to do what those who are a little older than themselves are doing. Five-year-olds aren’t particularly interested in emulating adults; adults are too far ahead of them, too much in a different world, to be effective models for 5-year-olds. But 5-year-olds do very much want to be like the cool 7- and 8-year-olds they see around them. And the 7- and 8-year-olds want to be like the 10-year-olds. And so on. That’s how children grow up.

Young children learn from older ones even when they are not interacting with them. They learn just from watching and listening.

How Age Mixing Benefits the Older Children

Age mixing benefits the older children at least as much as it benefits the younger ones. Interactions with younger children allow the older ones to be the mature partners in relationships and to practice nurturance and leadership. Cross-cultural studies have revealed that boys and girls everywhere demonstrate more kindness and compassion toward children who are at least three years younger than themselves than toward children closer to their own age.

There is even evidence that experience with young children causes older children to become more compassionate not just to the young children, but also to peers their own age. Here are two examples.

- Babysitting. Boys who have extensive babysitting experience have been found to become kinder and less aggressive in their interactions with their own peers than do boys who do not have such experience.

- Tutoring. Tutoring studies in conventional schools — where older children help younger ones with their lessons — commonly reveal increases in measures of responsibility, empathy and altruism in the tutors.

Age mixing also allows older children to learn through teaching. In age-mixed play, older children often find themselves in the position of explaining concepts to younger ones. To teach any concept, one must first clarify it in one’s own mind, to put it into words that the learner can understand. In the process of such clarification, the teacher may gain a more solid understanding of the concept than he or she had before. The requirement for clarification may be present especially in cases where the status or authority differences between teacher and learner are not too great, so the learner feels comfortable questioning and challenging the teacher. In such cases, teaching and learning become bidirectional activities, in which “teacher” and “learner” learn from one another. Here are examples my graduate student Jay Feldman and I observed in research on children’s mixed-age play.

- Discussions boost understanding. We observed many instances of back-and-forth discussions between older and younger children that seemed to expand the understanding of both individuals. For example, when older children taught strategy games such as chess to younger ones, the questions asked by the younger ones often led the older ones to stop and think before answering. They had to reflect on their own understanding of why one move was better than another before they could articulate an answer.

- Play is more nurturing and creative. Our research also indicates that age-mixed play is generally less competitive, more nurturing and more creative than same-age play. Age-mixed play is not about winning and losing — the older one could always win if he or she wanted to — but is about having fun and learning. The players need to work out creative ways of playing, so that all involved are stretching their own skills and having fun, while, at the same time, helping the others to have fun.

Age mixing allows older children to learn through teaching.

I end now, with a scene I observed many years ago at a school that fosters age-mixed play, a scene that illustrates especially the creativity that can arise in such play:

“I was sitting in the playroom pretending to read a book but surreptitiously observing a remarkable scene. A 13-year-old boy and two 7-year-old boys were creating, purely for their own amusement, a fantastic story involving heroic characters, monsters and battles. The 7-year-olds gleefully shouted out ideas about what would happen next, while the 13-year-old, an excellent artist, translated the ideas into a coherent story and sketched the scenes on the blackboard almost as fast as the younger children could describe them. The game continued for at least half an hour, which was the length of time I permitted myself to watch before moving on. I felt privileged to enjoy an artistic creation that, I know, could not have been produced by 7-year-olds alone and almost certainly would not have been produced by 13-year-olds alone. The unbounded enthusiasm and creative imagery of the 7-year-old, combined with the advanced narrative and artistic abilities of the 13-year-old, provided just the right chemical mix for this creative explosion to occur.”

Older children don’t have to be forced to play with younger ones, or vice versa, but must simply be given the opportunity to. My research and that of my graduate students has shown that, given a choice, children often prefer to play with others who are older or younger than themselves. Something in their DNA drives them to it. In their bones they know that such play is especially fun, and especially beneficial.

Peter Gray, Ph.D., is a research professor in the department of psychology at Boston College. Read more from Dr. Gray about the role of play in kids’ development in his book “Free to Learn: Why Releasing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life” and on his Psychology Today blog.